The Samaritan and the Victim: Questions from Three Perspectives

In the previous post, we discussed the question, “Who is my neighbor?” There we examined the question posed by the lawyer. His question is one that we all may come to ponder on as we read the parable. But it is not one with an obvious answer. I say that because the parable is often thought of as an ethical mandate; it’s often thought of as a case for Christian charity. This is embedded in the parable but is that the main concern of Jesus in presenting the parable? The lawyer first came to Jesus with a spiritual and existential question: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” In the previous post, I mentioned that the responses of the lawyer to Jesus’ counter-question, “What is written in the law?” are one and the same. To love God and to love neighbor are part of the entwined aspects of humanity, which is the physical and spiritual dimensions. Christianity is not like the ancient gnostic religion which imagined the physical world as evil and the spiritual realm as true goodness. Jesus Christ, by his very incarnate nature of “God in flesh”, revealed the redemption of the creation as a necessity of God’s salvation plan.

Thus we come to the meaning of the parable wrapped up in questions on the salvation plan of God. Who is in need of a neighbor? What exactly is a neighbor?

Who needs a neighbor?

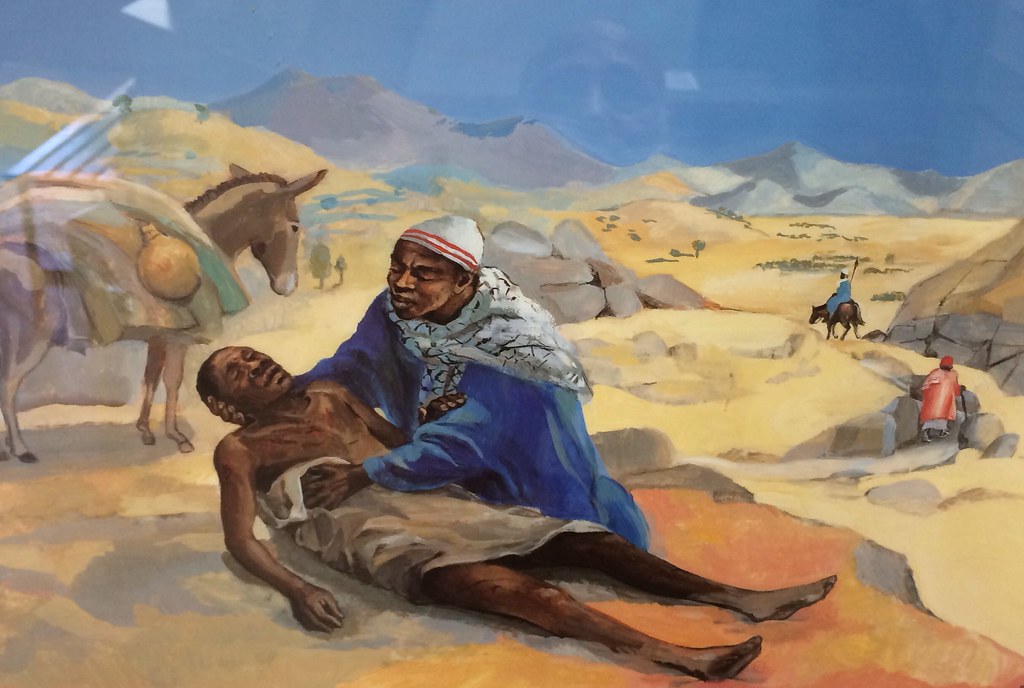

A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and took off, leaving him half dead. (Luke 10:30)

The condition of the man who was robbed was pathetic. He was totally immobilized, with hands and legs stretched out in agony. He was probably too weak to cry for help, if he was even conscious. But suppose he was conscious; then all he could do was watch for anyone to help. When he heard the steps of the priest, his hope rose. He knew he would get the help he needed. And from a fellow Jew. It was a priest; "How wonderful," he must have thought. But those steps faded away. A while later came the sound of the Levite's feet. Once again, hope arose but was quickly dashed. Another fellow countryman came and went. Both of them even jumped to the other side of the road to avoid him. Such was his pitiful condition. Much later, a Samaritan came. "Well, there's no hope there", the man thought. "He is a Samaritan; they don't have anything to do with the Jews." But help comes in unexpected ways.

Here is the twist in the story: Not only did the Samaritan stop and help this victim, he went above and beyond his moral duty. He only had to take him back to the edge of civilization. Instead, he uses his own wine, oil, and cloths to bandage him. He placed him on his own donkey and walked beside. He stayed the night at the inn, attending the needs of this wounded stranger. After paying for their stay, he basically gives the innkeeper a blank check, saying, "Take care of him, and when I come back I will repay you whatever more you spend." He placed no limits on his time or his money. It was not a common man who did this.

This parable is often interpreted today as a case of social justice. But even that is criticized today. The Lutheran priest Rev. Brian E. Konkol, in an article titled "When Robbers And Innkeepers Profit From Good Samaritans" points out that a simple call to charity to address the needs of the poor and oppressed in society fails to address the systemic problems. However, the only conclusion he can come to is to say, "May we be tormented by the ideal of a common good, and by God’s grace, may we trust that justice will indeed prevail." But which sociopolitical theory or whose philanthropic effort is the right one? Nations, NGOs, and individuals are still trying to solve the systemic problems. If that is the case, then should we stop insisting on trying to address the deep injustices of society? Of course not. Many societies have made much progress in building a better world; but at the same time, many things remain the same. All religions try to seek the common good; many spiritualities try to get at the heart of the supra-existential question. But it is only the revelation of Jesus Christ which truly reconciles the broken world and the brokenness of each person with the purposes of God. This is the heart of the parable.

Christ the True Neighbor

Like the victim, we look expectantly at the priest and the Levite, the fellow neighbors in that society. But no familiar person stops to help. Help came unexpectedly from the least likely person. Today, we may be expecting help from certain people or we may expect God’s help in a certain way. Our perspective doesn’t see God’s plan for us. We have disconnected the sacrifice of Jesus Christ from our reality today by relegating Jesus Christ to the 1st century. The Apostle Matthew ends the Gospel with “And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age. (Matt 28:20)” What Christ has done for us two-thousand years ago is transformative for us today. His sacrifice on the cross assures all who trust in Him today of their sure salvation. Job prophesied in the midst of his affliction: “I know that my redeemer lives, and that in the end he will stand on the earth. And after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God. (Job 19:25-26)” The mystery of His sacrifice is incomprehensible today, just as it confounded many in the 1st century also. This revelation is the timeless and relevant message of the Gospel. From this foundation radiates much of the ethical practices of the Gospel. Not the other way around. Thinking that the empathy of the Samaritan is a call to sacrificial ethics falls short of the imposing message of the parable.

Not many can do as the Samaritan did, nor can we drive out the systemic problems like other ethicists prod us to. We risk calling Jesus and His teachings as “elitist ethics,” and relegate Jesus to the cupboard of saintly teachers of impossible moral standards. Instead, knowing that Jesus Christ has set you free from the bondage of sin and Satan will free you to seek the face of God. It frees you to show God to the broken peoples through the proclamation of the Gospel. It frees you to reach out and tend the physical wounds and mental anguish of those suffering from poverty, addiction, and the cache of brokenness in this world. You are not concerned whether the work you do is making an impact because you are offering it in the name of the God who has already planned the repair of the whole creation. It will make an impact by bringing someone a step closer to their Savior.

Who needs the neighbor? It was I who needed the Neighbor. The True Neighbor has saved me and healed me. Now I can also be a neighbor, following the footsteps of Him who saved me from death and destruction.

[Photo Credit: tim kubacki; https://www.flickr.com/photos/timkubacki/10724062065]